Semantic Interoperability and Ontologies

These reflections are based on the work done in the Design and Data project, where we explored the use of semantic interoperability in the design process.

The Challenge of Interoperability

Building design and construction professionals have suffered greatly throughout the years with lack of interoperability between tools when they need to exchange models between the disciplines. Ideally fast iterations are needed to evaluate how the proposed solutions will affect various aspects such as the structural model, energy performance, daylight, acoustics and the list gets longer and longer as the range of available software modules increases. Often the manual work to "fix" the model after importing it into the professional tool of choice is tedious and time consuming, which can risk a lack of updated information in the model.

Digital Twins and Data Complexity

In a context of digital twins, that are supposed to be a "living digital replica" of a phenomenon that is covered in a specific context, the challenges for the design process is a delicate problem as a complex amount of data needs to be dealt with in faster iterations than in existing buildings or infrastructure.

Evolution of Data Exchange Formats

XML and Industry Standards

From a technical point of view the semantic interoperability got a lot of attention in the industry as the XML format got popular in the early 2000s. This text based format is relatively easy for humans to understand as it is using "tags" with ordinary words instead of binary data, which also was a beginning of a new era of semantics in the wording and structure of the data exchanged in the industry.

Still today the XML schema is very common in the industry to make sure that we agree on the semantics of the data we exchange. The CityGML format being a very popular choice in the context of city information modelling (CIM) uses the XML schema to make sure that we use the exact same words when we describe the data we exchange. Worth mentioning is the IFC, which uses an XML schema derived from the EXPRESS schema source, another standard way of formalising the data we exchange between our software systems.

Challenges with Existing Standards

When we evolve into digital twin enabled systems it makes sense to use existing commonly used standards as there are more and more data sources that need to come together in an integrated environment.

The problem of these schemas is that in a very fast changing world of digitalisation, the additions to the schemas need to go in a more and more rapid pace, also taking into account that software systems might need to update the software when additions are made. It's already shown that the development of schemas takes a long time for the authoring organisations that need to agree among the experts internally and also adhere to the big actors in the industry that already have implementations that should be taken into account. On top of this, standardisation efforts take even longer time, as the workload is high on the most notable standard organisations.

Custom Solutions and Emerging Frameworks

This leads to software manufacturers creating custom new schemas or information models over and over because the implementation requires specific tailor made additions that are not covered by the open format or standard. Going into digital twins or Industry 4.0 where there are many systems, potentially from many different actors or vendors that need to be interconnected there are emerging frameworks that solves the problem by being flexible and extensible. One example is the OPC UA standard that uses companion information models modelled in XML schema to continuously extend modules where needed.

Early Stage Design Challenges

Continuing into the context of digital twins we need schemas, as in most software systems, to make sure that the data we are exchanging is valid. In early stage design the challenge is how to express abstractness at the desired level of the design process and still make sure that we can exchange proper models that will integrate in an existing digital twin system. There is also a large amount of aspects to weigh into design at early stages, in fast iterations. It's hard to use IFC and CityGML formats as these are covering an extensive amount of descriptions, yet lack a lot of consideration for early stage planning, at least according to the support in different tools.

Design and Data Framework Approach

In the Design and Data project framework we also need to take schemas into account to make sure that what we decide to send between actors in the design process, and also through a connected urban digital twin is valid data. But how should we cover all the considerations for early stage design and still use an existing exchange format or standard? To extend an existing model every time we have a new consideration would lead to major disruptions in the process and require technical expertise to ensure consistency of the model. This is why we propose a dynamic and agile formalisation process where harmonisation of data is done through an organic change management process that can grow from the specific project to company level and partner consortia.

Change Management and Human-Centric Design

As we know from XML the terminology and structure used is fixed from each revision of the schema produced. We need change management in place to allow the schema to change continuously and help to keep track of what version we are using and how to upgrade existing data without inflicting inconsistent parallel models in the system. Software tools, and certainly upcoming AI support, can help to identify and even propose semi-automated fixes to these inconsistencies. This means that we are building a framework that is primarily suited for humans to understand the semantics and in which collaboration can be improved by ensuring that humans talk about the same thing when exchanging data between systems. This goes into contrast to the existing standards and data formats that are so complex that they need expertise to be dealt with, leaving out most professionals that are not trained as technical experts.

The Semantic Web Stack

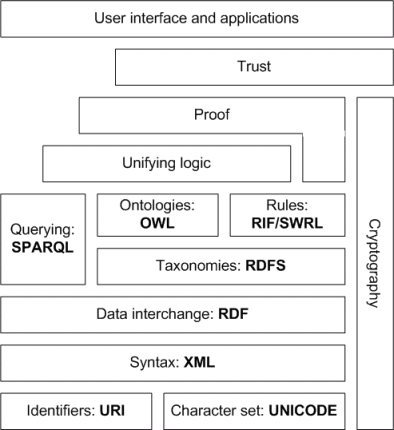

To create a flexible framework we need to go beyond schemas and look into a higher level abstraction of how we describe the data. A good source of information is the semantic web stack which was created by the experts of the world wide web to solve the problem of interoperability, harmonisation and inconsistency in data sources online.

Figure 1: The semantic web stack consists of standards for semantic data on the web (source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Semantic-web-stack.png)

As we can see, going up one level in the stack we can use rules and relationships between entities to be able to connect logical terms. In this way we can use different words meaning the same thing by definition, and let logical inference help us to deduct this. The OWL standard is the ontology language of the web in which many rules can be defined to make sure that we are consistent in the data we exchange.

Modern Data Exchange with JSON and JSON-LD

To transfer data through modern APIs it is common to use the JSON format. So does Speckle, and although Speckle uses an internal data format to represent geometry the system is data agnostic and does not take semantics into consideration. This means that we need to create additional implementations to use our framework with Speckle. Examples of the JSON format payloads can be found in the sections on Speckle and Rhino/Grasshopper workflows, but here a more general description of JSON capabilities together with semantic data payloads will be described. This is also compatible with Speckle and a suggested approach for the framework as it is built on an incremental process of building true interoperability using standard approaches, yet allowing maximum flexibility.

JSON-LD is a JSON addition that is compatible with the semantic web stack. Using JSON-LD it is possible to link data between different online resources and descriptions and make sure that something truly is what it appears to be. This is a way for one project or company to define their own terminology, data assets or data resources. Using a separate "context" definition it's possible to make two exact same words to be semantically different. Being distributed online, the reuse of this kind of descriptions can be maximised as the way to distinguish between the definitions can use URLs in the namespace. It means that the resource is actually hosted online at the place of its description.

{

"@context": {

"building": "http://example.org/building/",

"space": "http://example.org/space/",

"rdfs": "http://www.w3.org/2000/01/rdf-schema#",

"name": "rdfs:label",

"hasFloor": "building:hasFloor",

"hasRoom": "space:hasRoom",

"area": "space:area"

},

"@type": "building:Building",

"name": "Office Tower A",

"hasFloor": [

{

"@type": "building:Floor",

"name": "Ground Floor",

"hasRoom": [

{

"@type": "space:Room",

"name": "Reception",

"area": {

"@value": "120",

"@type": "space:SquareMeters"

}

}

]

}

]

}

Figure 2: JSON-LD contains a context that maps out the source to different terms to avoid ambiguity (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/JSON-LD)

Framework Implementation

Terminology and Data Management

We define the terminology as we bring in or create data in the project. This can be done by reusing terminology from other projects, company wide descriptions, existing information models or standards. The incremental approach will make it easier to discuss semantics as the project progresses. The flexible approach will make it possible to change terms during the process and combine different vocabularies. The code revision inspired approach will make it possible to version the schema continuously.

Storage and Validation

To store the temporary semantic descriptions, a data agnostic JSON based system like Speckle can be used. In the project we used a Speckle branch to store the schema separately from the instantiated objects. In this way a "validator app" can be used where the objects can be validated according to the schema. This could be done optionally if the creative process should not be disturbed, but it would definitely be done before exchanging the data to another tool or system.

Semantic Framework Sustainability

For a sustainable semantic framework it's good to make sure that the reuse is maximised between projects and actors in data value chains. Although the framework also has maximum flexibility, it is suggested to take some extra steps when a successful semantic flow has been implemented to prepare it for reuse in an upcoming project, or share it as a proposal for wider agreement or harmonisation with existing vocabularies.

Application and Domain Levels

When we define terminology in a project scope we can call this the "application level" which means that from the new project data description created and the tools that are used we are in the scope of the application, which means that the software will call entities different things and when we are creating new instances of object and give them semantic connection we are not connected to "the world outside". However for project data it would be preferable to connect to the specific and reusable "domain level" descriptions. In early stage design we could have many domains to relate to and our objects could belong to several domains at the same time. We would for example like to reuse our geometries for energy simulation, structural load calculation, acoustics and so on. But moving into each of these domains the geometry might be used in completely different ways and require different semantic connections. This is a challenge that is not solved properly in the building construction industry.

Namespaces and Logical Rules

If we add namespaces, or "prefixes" to our terminology we can use the same words meaning different things in different contexts. This is also a technical requirement for ontologies, where it otherwise would be impossible to distinguish two identical words from each other. But when we add logical rules to this mix it is also possible for both humans and machines to know that two words have exactly the same meaning, or maybe they can be defined explicitly as not the same. Elaborating on this concept of logical rules we can use software to reason automatically, thus warning us about inconsistencies in our data interoperability flow. Moreover we can expand the layering approach to abstract the data into a "middle level" ontology. At this level we can connect things from different domains to their more abstract meaning, yet making sense for humans. The software can still use the logical rules to infer that some things are the same, yet described differently in our mishmash of formats from different formats or standards from different domains. At this level of abstraction a professional ontologist can make sure that the ontology aligns with a top-level ontology. A top level ontology is consistent with first order logic and can be proven mathematically. When connections are done from application level, through different domain levels and up to top level ontology we can be sure that the system is interoperable, and a software tool can also be used to help to check this consistency.

Term Generality

Figure 3: Levels of ontologies provides a system that enables flexibility in adoption (Source: Cummings, Joel. "DCO: A Mid Level Generic Data Collection Ontology." (2017).)

Conclusion

In the proposed framework any terms that are commonly used in the industry in early stage design can be used instantly by semantic connections. The process is iterative and uses code revision principles for versioning. The semantic descriptions need to be formalised at times using namespaces and be distributed to reach beyond the application level. To reach true interoperability it needs alignment with existing abstract interoperability layers.